Formative Program Planning

Form a planning and evaluation team

Before implementing and evaluating your program, it is important to thoughtfully and thoroughly plan both the program and evaluation activities. If possible, consider creating a team with other staff, partners, and stakeholders to focus on planning and evaluation. A team can bring unique and diverse ideas to the table, ensure the needs of various stakeholders are being met, and allow tasks to be divided up.

Note: You may not have the time and resources to form a planning and evaluation team or use some of the more rigorous evaluation designs and methods in the next chapters. If this is the case, select planning and evaluation approaches that you think are feasible and realistic given your resources and constraints. You can also go straight to the “Toolbox” in Chapter 7 for quick tips and tools you can customize and use to help plan and evaluate your program activities.

Select a team leader

If you decide to form a planning and evaluation team, consider selecting a planning and evaluation team leader to facilitate and coordinate team activities. Having a “go-to” person to coordinate activities and provide leadership throughout the development and implementation of the program can help things operate as smooth as possible. The team leader can function as a point person to ensure that important decisions are made when necessary, without the confusion of who has the responsibility to make final decisions. Remember, it is not the job of the team leader to do everything. The team leader has the responsibility to ensure important tasks are taken care of and completed, and this is usually done through delegating to other team members or staff. Below are important things to think about when selecting a team leader.

An effective team leader:

- Understands the overarching goals and priorities of the program and what tasks must be accomplished.

- Has strong interpersonal skills and is able to communicate and work effectively with staff and partners.

- Is good at delegating responsibilities and tasks to others.

- Is supportive and encouraging of others.

- Is able to refer to other individuals with specific expertise in program development, evaluation, or food safety for recommendations or insight.

- Has a realistic understanding of program resources and limitations but also encourages staff and partners to be creative and innovative when planning and strategizing.

- Understands and teaches the importance of using research- and evidence-based strategies when implementing consumer food safety education campaigns and interventions.

- Is flexible and able to acknowledge both the strengths and weaknesses of the program.

- Uses evaluation data and participant, staff, and partner input to continuously improve the program.

Build partnerships

If you are forming a planning and evaluation team, think about stakeholders or partners you might want to work with or have represented. Consider including a key informant or community expert from the target audience to provide valuable insight about the individuals you are trying to reach. Stakeholders can include individuals who will help implement the program, those who the program aims to serve (target audience), and individuals who make decisions that impact food safety. You may also want to think about inviting or hiring an experienced evaluator to join your team. A benefit from hiring an external evaluator, instead of solely relying on staff members, is the potential of reducing bias and increasing objectivity of throughout the evaluation process [15,17,21]. Below is a list of potential partners or stakeholders to consider inviting to join your team. Potential partners:

- Food safety researchers

- Health professionals

- Health educators

- External evaluators

- Key informants or representatives from your target community

- Previous participants of your program if applicable

- Teachers

- Representatives from local grocery stores or supermarkets

- Representatives from local health organizations or health departments doing work related to food safety

- Staff from local food banks, community centers, or Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) clinics

There are nine key elements to a successful partnership [5]:

- “Provide clarity of purpose

- Entrust ownership

- Identify the right people with whom to work

- Develop and maintain a level of trust

- Define roles and working arrangements

- Communicate openly

- Provide adequate information using a variety of methods

- Demonstrate appreciation

- Give feedback”

Identify the food safety education needs of the target audience

Before planning program activities, you will need to figure out exactly who your target audience is, the barriers and challenges they face in implementing safe food handling practices, and their specific food safety needs so that you can design a need-based program.

Identify the target audience

First, identify your target audience or the segment of the community that your program will focus on and serve. The target audience can consist of individuals who are most vulnerable to foodborne illness, individuals who will most benefit from your materials and resources, and/or people who can function as gatekeepers and will use your program to not only benefit themselves, but others as well. For example, focusing on parents and increasing their knowledge about food safety may lead them to model and teach safe food practices to their children.

If you already have a behavior in mind, your target audience can be individuals who do not already practice that behavior [4]. For example, if the desired behavior is correct handwashing, the target audience can be individuals who wash their hands incorrectly [4]. In this case, since you have already identified the target behavior, you will then need to conduct some research or a community needs assessment to determine what part of the population tends to wash their hands incorrectly. The group that you identify will be your target audience.

Alternatively, you may wish to start by conducting some food safety research in order to identify vulnerable populations that you might want to select as the target audience. For example, you may decide to do some formative research and find that higher socio-economic groups are associated with higher incidence of Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Escherichia coli, or that low socio-economic status (SES) children may be at greater risk of foodborne illness [3,8,28]. This information could help you narrow down your target audience by statuses, and you can then use tools such as the interactive Community Commons maps (http://www.communitycommons.org/maps-data) to identify specific populations or geographic locations in your community to focus on.

You can also select your target audience by identifying a segment of the community or a specific setting to focus on (parents or teenagers in a specific school district, residents in a specific zip code, or residents of a senior center). Once the setting has been selected, conduct a needs assessment to identify what target food safety behaviors you should focus on.

Examples of populations you could target:

- Older adults

- Parents

- Teachers

- Food service staff or volunteers

- Assisted living aides

- Vulnerable populations: children, older adults, pregnant women, individuals with weaker immune symptoms due to disease or treatment [11]

Conduct a needs assessment

In your needs assessment, you will want to find out what factors influence your target audience’s food handling practices. Identifying these factors will help you figure out what strategies you need adopt to address specific barriers and promote safe food handling behaviors. You don’t need to start from scratch. Do some research to find out what information and resources already exist on the behavior or population you want to focus on. This can help you identify important food safety factors to address in the assessment or gaps that you might want to further investigate.

Below are important food safety factors you could explore in your needs assessment and examples of questions you might want to ask [adapted 12].

- Access to resources: Are there any resource barriers that prevent the target audience from adopting certain food safe practices? Examples include: lack of thermometers, soap, or storage containers.

- Convenience: Are there any convenience barriers, such as time or level of ease, the target audience thinks prevents them from implementing safe food handling behaviors?

- Cues to action [7]: Are there any reminders or cues the audience thinks would motivate them to engage in certain food safe practices? Are there any that they have found to be successful in the past?

- Knowledge:

- Inaccurate knowledge or beliefs: Does the target audience have any inaccurate beliefs related to food safety and foodborne illness?

- Specific knowledge: Does the target audience have any specific knowledge gaps related to food safety and food handling behaviors?

- Knowledge – Why: Does the audience understand why a specific behavior is recommended and how it prevents foodborne illness?

- Knowledge – When: Does the audience understand exactly when and under what circumstances they should engage in a specific food handling behavior?

- Knowledge – How (Self-Efficacy) [7]: Does the audience know how to engage in the specific behavior? Do individuals believe they are capable of engaging in the behavior?

- Public policy: Are there any policies in place that prevents or makes it more challenging for the target audience to engage in a recommended behavior? What existing policies influence the audience’s food safety knowledge, attitudes, or behaviors?

- Sensory appeal: How does the smell, appearance, taste, and texture of a food influence the target audience’s food handling practices?

- Perceived severity [7]: Is the audience aware of the short- and long-term consequences of foodborne illness?

- Social norms and culture: What kind of food safety attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors does the target audience’s social circle, including family and friends, possess and engage in?

- Socio-demographics: What is the demographic and socioeconomic status of the target audience? Examples of demographic factors include gender, ethnicity, age, and education level.

- Perceived susceptibility [7]: How susceptible does the audience feel they are to foodborne illness resulting from food handling practices at home?

- Trust of educational messages: How trusting is the target audience of consumer food safety messages? Do they find sources of these messages to be credible?

When planning “Is It Done Yet?” a social marketing campaign to increase the use of thermometers in order to prevent foodborne illness, a specific audience —upscale suburban parents —was identified and targeted. This target audience was carefully chosen for specific reasons, such as being more likely to quickly move through the stages of behavior change to adopt the new behavior, its tendency to be influencers and trend setters, and because of its propensity to learn and use new information.

When planning “Is It Done Yet?” a social marketing campaign to increase the use of thermometers in order to prevent foodborne illness, a specific audience —upscale suburban parents —was identified and targeted. This target audience was carefully chosen for specific reasons, such as being more likely to quickly move through the stages of behavior change to adopt the new behavior, its tendency to be influencers and trend setters, and because of its propensity to learn and use new information.

Geodemographic research was conducted to get to know this population to learn about its interests, characteristics, and where it accesses information. Observational research in a kitchen setting was also conducted to learn about how the parents use thermometers and handle foods. This helped program planners identify important barriers that would need to be addressed in the campaign and gather information to help test and develop campaign messages. Messages were pilot tested at a “special event” held in a popular home and cooking store where participants were able to provide feedback on several message concepts. Following the event, follow up focus groups were conducted to select the final campaign slogan, “Is it done yet? You can’t tell by looking. Use a thermometer to be sure.”The campaign’s overarching goal was to increase the target audience’s awareness that they need to use a food thermometer and as well as their intentions to use a food thermometer. Specific objectives for the campaign were identified as:

- Leverage outreach through partnerships

- Saturate the target audience’s market with messages about thermometer use

- Use free and paid media to disseminate messages

- Hold community events at stores, schools, festivals, and other venues

- Collect and analyze pre- and post-test data related to the campaign

Before implementing the campaign, baseline data was collected through a mail survey that aimed to identify where the target audience was in stages of behavior change. Following the campaign, data analysis of pre- and post-test surveys indicated that among parents that did not always use a thermometer when cooking, 50 percent considered using one. In addition, 15 percent of individuals in the target audience who were previously not thinking about or using a food thermometer became aware of the need to use one. The proportion of the target audience that used thermometers (sometimes, most of the time, and all of the time) also increased by around 9 percent.

USDA, Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS). (2005). A report of the “Is It Done Yet? Social marketing campaign to promote the use of food thermometers. U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service. National Food Safety & Toxicology Center at Michigan State University. Michigan State University Extension. Michigan Department of Agriculture (Funding Provider for Michigan). Retrieved from: http://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/wcm/connect/0123b79c-ad0e-4bea-9d1d-049da51cb10a/IsItDoneYet_Campaign_Report_120105.pdf?MOD=AJPERES

Utilize behavior theories

Using a theoretical framework for understanding how and why individuals engage in behaviors can be useful to identify what questions to ask in your needs assessment and to identify effective strategies to use to design and implement your program. Behavior theories can also help you narrow down your evaluation approach and the main questions you want to answer to determine the impact and outcomes of your program.

Below are examples of two behavior theories that have previously been applied to consumer food safety studies:

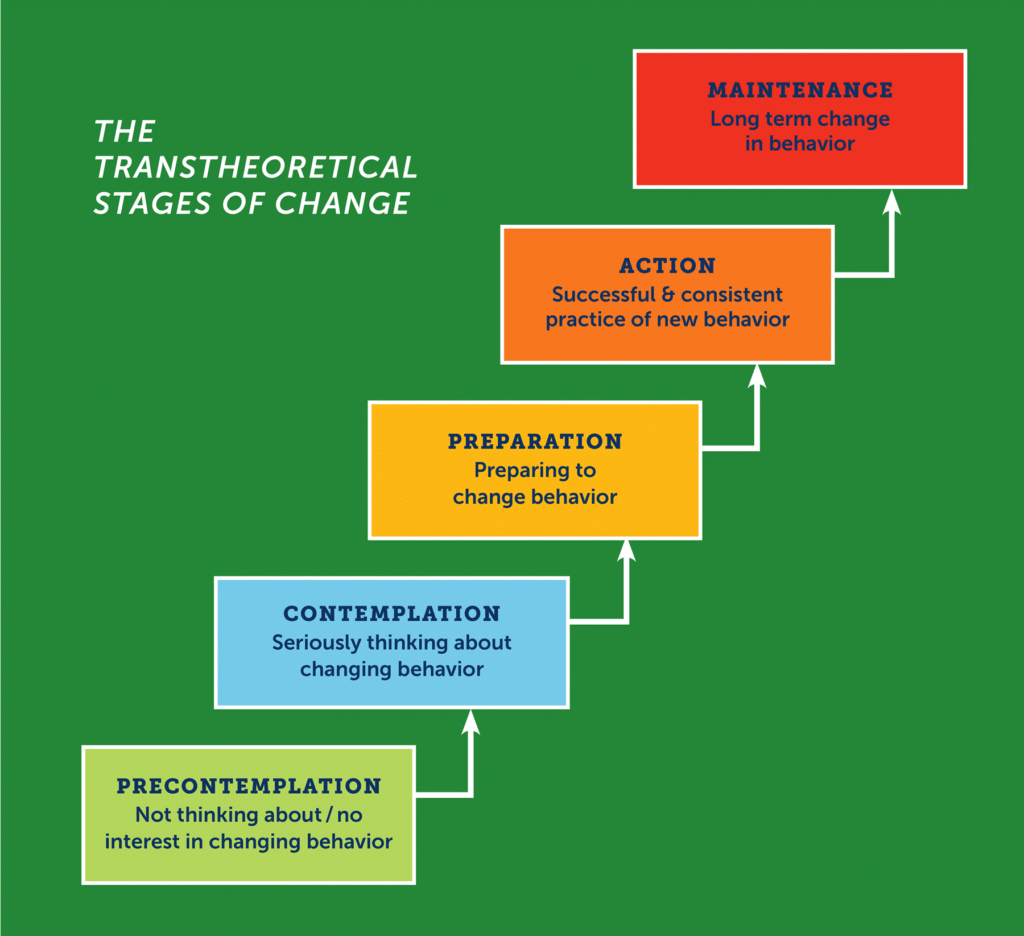

Transtheoretical Model

The Transtheoretical Model, or stages of change theory, provides a framework for the stages an individual can experience before successfully changing behavior [23]. There are five stages:

- Precontemplation – when an individual is not thinking about changing behavior and may be unaware of the consequences of his/her actions [23]

- Contemplation– when an individual has not taken any action yet, but is seriously considering changing his/her behavior in the next 6 months [23]

- Preparation – when an individual is preparing to make a behavior change within 1 month [23]

- Action when an individual has been successful and consistent in engaging in the new behavior in a 1 to 6 month period [23]

- Maintenance – when an individual has engaged in behavior change for 6 or more months [23]

Understanding what stage of change your target audience is in can be valuable in determining how to strategically communicate with them. For example, the needs of individuals that are in the precontemplation stage and not thinking about food safety might be different from individuals in the preparation stage. For those who are in the precontemplation stage you might need to put a greater emphasis on why safe food handling behaviors are important in the first place. Individuals in the contemplation stage may already understand why food safety is important and might require more support in terms of encouragement or helpful tools teaching them how to adopt the new behavior.

Other key constructs of the Transtheoretical Model are decisional balance, or what individuals perceive are the pros and cons of engaging in a specific behavior, and self-efficacy, how confident the individual is in his/her ability to engage in the behavior [23]. Exploring these constructs can help you understand more about your target audience, its beliefs related to consumer food safety, and how to best promote safe food handling practices to the group.

To examine the impact of a food safety media campaign targeting young adults, college students from five geographically diverse universities were recruited to participate in a pre- and post-test and a post-test only evaluation. Pre-test data was collected 2 to 4 weeks before the campaign began and post-test data was collected one week after the final week of the campaign. Recruitment efforts included Facebook flyers, ads in the school newspaper, and announcements made in student listservs and in class.

To examine the impact of a food safety media campaign targeting young adults, college students from five geographically diverse universities were recruited to participate in a pre- and post-test and a post-test only evaluation. Pre-test data was collected 2 to 4 weeks before the campaign began and post-test data was collected one week after the final week of the campaign. Recruitment efforts included Facebook flyers, ads in the school newspaper, and announcements made in student listservs and in class.

The objective of the evaluation was to find the campaign’s impact related to food safety self-efficacy, knowledge, and stage of change. Stage of change, a construct from the Transtheoretical Model, was assessed using a questionnaire item asking participants to identify what statement best described their stage of change related to food handling. Response options included:

- I have no intention of changing the way I prepare food to make it safer to eat in the next 6 months (pre-contemplation).

- I am aware that I may need to change the way I prepare food to make it safer to eat and am seriously thinking about changing my food preparation methods in the next 6 months (contemplation).

- I am aware that I may need to change the way I prepare food to make it safe to eat and am seriously thinking about changing my food preparation methods in the next 30 days (preparation).

- I have changed the way I prepare food to make it safe to eat, but I have been doing so for less than the past 6 months (action).

- I have changed the way I prepare food to make it safe to eat, and I have been doing so for more than the past 6 months (maintenance).

1,159 students took the pre-test (about a half, 552, lost to follow up) and 650 individuals completed the post-test, resulting in 607 matched pre- and post-tests. Evaluation data indicated that following the campaign, there was an increase in self-reported food safety knowledge and skill, actual food safety knowledge, self-efficacy, stage of change, and self-reported handwashing behaviors.

Abbot, J.M., Policastro, P., Bruhn, C., Schaffner, D.W., & Byrd-Bredbenner C. (2012). Development and evaluation of a university campus-based food safety media campaign for young adults. Journal of Food Protection, 75(6), 1117-1124

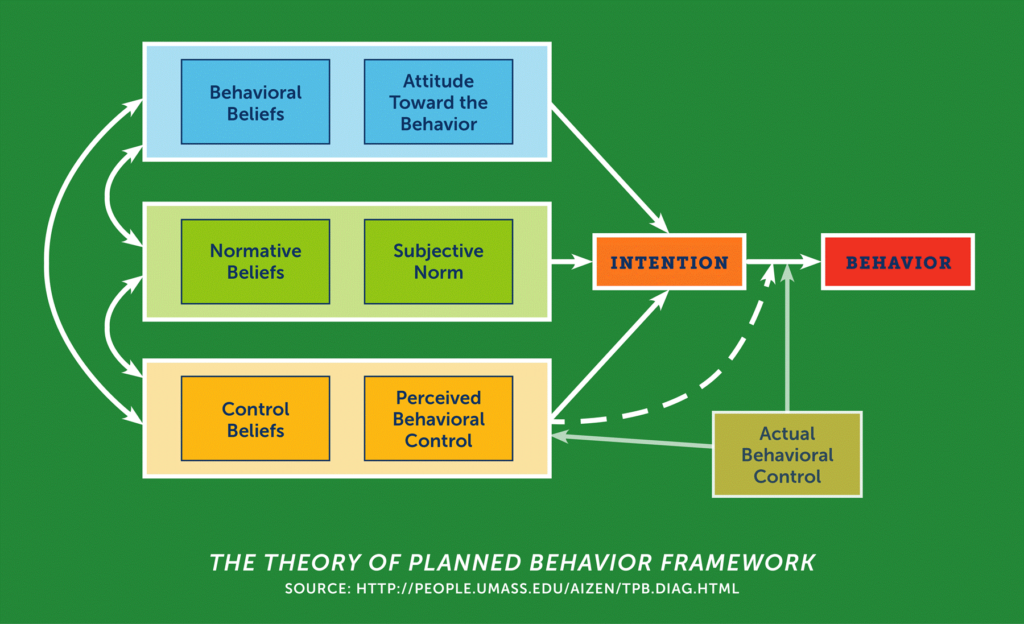

Theory of Planned Behavior

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) provides another framework for understanding behavior. The TPB is founded on three constructs that influence an individual’s intention to engage in a particular behavior. They are: attitudes towards a specific behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, or the perceived ability to make a behavior change or carry out a specific action [2].

By focusing on intent, we can understand the motivational factors that influence behaviors [2]. In general, the stronger a person’s intent to engage in a specific behavior, the more likely he/she will engage in the behavior [2]. Intent is influenced by attitudes, which develop as a result of personal beliefs related to a particular behavior [2,13]. A more positive or favorable attitude towards a behavior can result in greater motivation or intent to engage in the behavior [2]. Normative beliefs and subjective norms, also influence intent, because individuals are often concerned about whether or not friends, family, or others within their social circle, would disapprove or approve their engagement in a particular behavior [2].

An individual must also have the necessary resources and opportunity to actually engage in the particular behavior [2]. A person must not only have motivation and intention to make a behavior change, he/she must also have the actual capabilities to make the change and perceive that he/she has the capabilities to successfully make carry out the behavior in question.

Exploring these constructs can help you understand your target audience’s intentions to engage in safe food handling practices, as well as whether or not, and how, it is motivated to do so. Understanding specific factors related to attitudes, norms, and perceived behavior control can provide insight into what strategies may be effective in motivating your target audience’s intentions to adopt safe food handling behaviors.

In one study, the Theory of Planned Behavior was used as a framework to understand knowledge and behavior gaps related to food safety. Questionnaires were developed and administered to study participants to gather information on predictors of food thermometer use and proper handwashing, two important food safety behaviors.

Analyses of 544 questionnaires showed that measures of TPB differed for each of the two behaviors. For example, participants held more positive attitudes towards proper handwashing than use of a food thermometer. Participants were also more concerned with subjective norms related to handwashing than thermometer use, had more perceived behavioral control over proper handwashing than thermometer use, and displayed more behavioral intent to wash their hands properly than to use a food thermometer. Survey data also showed that perceived behavioral control was the strongest predictor of behavioral intent related to proper handwashing and use of a food thermometer. For thermometer use, the second strongest predictor was subjective norms and the second strongest predictor for handwashing was attitude towards the behavior. Overall, the study found the TPB to be useful in understanding food safety behaviors, particular proper handwashing and use of thermometers when cooking.

Shapiro, M.A, Porticella, L., & Gravani, R. B. (2010). Predicting intentions to adopt safe home food handling practices. Applying the theory of planned behavior. Appetite, 56(1), 96-103.

Identify core activities and messages

Once you have conducted your research and needs assessment to identify your target audience and the food safety behaviors you will focus on, you can start identifying the main elements of your program, such as what kinds of messaging and activities you will create and implement, and where the program will take place.

Identify program activities

Taking into account your resources and the needs and interests of your target audience, think about what kinds of strategies and activities will be most effective to achieve your education objectives. Consider using more than one education method to maximize reach and the quality of your program [9]. Most common education approaches in consumer food safety today include educational experiences that are interactive and hands on and mass media/social marketing campaigns that use multiple media channels and target a specific geographic location [12].

Below are ideas of consumer food safety education activities you could implement:

- Hold a free food safety workshop for parents at a local library or community center. Work with local schools to send out invitations and provide onsite childcare to encourage participation.

- Reach out to primary care physicians and determine how best to inform their patients about food safety. Provide educational messages and materials such brochures for them to hand out to their patients.

- Meet with teachers and school administrators and inform them of the importance of consumer food safety. Provide them with educational resources they can share with their students and work with them to incorporate food safety education in school curriculums.

- Develop a social marketing campaign with core messages that address the specific needs and knowledge gaps of your target audience (identified in the needs assessment). Work with local partners and stakeholders to support you in sharing and disseminating the messages.

- Hold a food safety festival for parents and children during National Food Safety Education Month in September. Plan interactive activities that are hands on and educational.

- Partner with local groceries and work with them to provide educational messages in their stores.

- Encourage work places to send weekly newsletters to employees on food safety topics, or create fun and educational food safety competitions [12].

Selecting a setting for your program can also help you narrow down and choose program activities. In this approach you would: select the setting for your program → conduct a needs assessment for the community within that setting → identify appropriate activities and strategies. Examples of settings for consumer food safety education activities include schools, public restrooms, health fairs, workplaces, and grocery stores.

Identify communication/delivery strategies and core messages

In your needs assessment, consider including questions that can help you identify how your target audience seeks out health information, what media channels it has access to, and what sources it finds to be credible and trustworthy. This information is key to ensure that educational messages are heard and trusted.

Potential delivery channels [12]:

- Traditional media (print, audio, video)

- “New” media (Internet, social media, video games, computer programs)

- Classroom-style lessons

- Interactive and hands-on activities

- Visual cues or reminders

- Community events and demonstrations

Crafting Your Message

When crafting food safety messages think about what you want people to know and what the primary purpose of your message is. There are three different types of messages you could use to influence food safety behavior [adapted 24]:

Awareness messages increase awareness about whatpeople should do to prevent foodborne illness, who should be doing it, and where and when people should engage in safe food handling practices. A key role of this type of message is to increase interest in the topic of food safety and to encourage people to want to find out more about how to prevent foodborne illness.

Instruction messages provide information to increase knowledge and improve skills on how to adopt new safe practices to prevent foodborne illness. These types of messages can also provide encouragement or support if people lack confidence in engaging in the new behavior.

Persuasion messages provide reasons why the audience should engage in a new food handling behavior. This usually involves influencing attitudes and beliefs by increasing knowledge about food safety and foodborne illness.

When crafting a persuasive message to encourage consumers to adopt a new behavior, there are three things to consider: credibility, attractiveness, and understandability. It is important that your target audience finds your messages to be [24]:

- Credible, accurate and valid. This is normally done by demonstrating you are a trustworthy source and providing evidence that supports your message.

- Attractive, entertaining, interesting, or mentally or emotionally stimulating. Consider providing cues to action messages that are eye-catching, easy to read, and include some amount of shock value [18].

- Understandable, simple, direct, and with sufficient detail.

Use appeals and incentives

Your message should include persuasive appeals or incentives to motivate the target audience to change their behaviors [24]. These can be can positive or negative incentives. Examples of negative incentives include inciting fear of the consequences of foodborne illness or negative social incentives such as not being a responsible care taker or cook for the family. Positive appeals demonstrate the positive outcomes for adopting new food safe practices, such as addressing strong physical health or being a good role model to family and friends. Using a combination of both positive and negative incentives can be a good strategy to influence different types of individuals. This is because it is probable that not all individuals of your target audience will be motivated by negative incentives, and not all by positive incentives.

Consider timing

The timing of when to disseminate messages is also an important factor to consider. Think about national or community events taking place that might peak the target audience’s interest in food safety and help you maximize the effectiveness or reach of your messages. For example, national health observances such as National Food Safety Education Month or National Nutrition Month®, might provide a great opportunity to promote your program or to share educational food safety information. The opening of a new grocery store could also a good opportunity to promote food safety. Your organization or program could partner with store owners and staff to provide food safety information during their grand opening and display food safety messages throughout the store.

Don’t reinvent the wheel

When developing core messages and educational materials you don’t always have to reinvent the wheel. Use science- and evidence-based materials that have already been created for consumer food safety education, such as resources developed by the Partnership for Food Safety Education on the four core food safety practices: http://www.fightbac.org/food-safety-basics/the-core-four-practices/.

Other food safety education materials you can use:

For consumers:

- Food Safe Families – http://foodsafety.adcouncil.org/

- Be Food Safe – http://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/portal/fsis/topics/food-safety-education/teach-others/fsis-educational-campaigns/be-food-safe

- Cook It Safe – http://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/portal/fsis/topics/food-safety-education/teach-others/fsis-educational-campaigns/cook-it-safe/cook-it-safe

For schools:

- Science and our Food Supply – http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/FoodScienceResearch/ToolsMaterials/UCM430366.pdf,

- Hands On – http://handsonclassrooms.org/

If you decide to use existing materials don’t forget to think about your target audience and how you may want to refine messages or materials to best serve its needs and interests. You should also take health literacy and cultural sensitivity into account.

Health literacy

Health literacy refers to a person’s ability to access, understand, and use health information to make health decisions. About 9 out of 10 adults have difficulty using everyday health information available to them, such as those in health care facilities, media, and through other sources in their community [10,20,25,27].

Things to consider:

- Incorporate a valid and reliable health literacy test, such as the Newest Vital Sign by Pfizer (http://www.pfizer.com/health/literacy/public_policy_researchers/nvs_toolkit), in your needs assessment to help you understand the health literacy levels of your target audience.

- Use plain, clear, and easy-to-understand language when writing educational consumer food safety information.

- Think of creative formats to share food safety messages such as video, multimedia, and infographics.

- Make sure messages are accurate, accessible, and actionable [6].

- Avoid medical jargon, break up dense information with bulleted lists, and leave plenty of white space in your documents.

- Use helpful tools such as the Center for Disease Control’s (CDC)’s Clear Communication Index (http://www.cdc.gov/ccindex/index.html), Everyday Words for Public Health Communication (http://www.cdc.gov/other/pdf/everydaywordsforpublichealthcommunication_final_11-5-15.pdf), and the Health Literacy Online Checklist (https://health.gov/healthliteracyonline/checklist/) to create and refine your content.

- When in doubt write at a 7th or 8th grade reading level or below [19].

- Conduct a pilot test of materials with representatives from the target audience to ensure that they are easy to understand and use.

Cultural sensitivity

When working with diverse or ethnic populations it is important to be culturally sensitive in your approach and interactions and when creating educational content.

Things to consider:

- It is not only important for you to translate food safety messages into another language when needed, but also to provide tailored information, examples, and visuals that are culturally relevant and appropriate [22].

- Take into account cultural beliefs, norms, attitudes, and preferences related to health and food safety.

- Work closely and collaborate with the target population to ensure you are addressing its specific needs [22].

- Hire members from the community with cultural backgrounds similar to your target population to help with recruiting, administering interviews, or facilitating focus groups to ensure that the data collection process is culturally sensitive and respectful [14,16,26].

- Request staff or colleagues with cultural backgrounds similar to target audience to review materials and messages for content that might include cultural assumptions or prejudice [16].

More communication tips

A few more tips for communicating consumer food safety information [12]:

- Make your messages specific to the target audience and address any food safety misconceptions the target audience may have.

- Provide powerful visual aids to help consumers visualize contamination. Use storytelling and emotional messaging to convey the toll of foodborne illness.

- Link temporal cues with food safety. For example, help consumers associate running their dishwasher with sanitizing their sponges and scrub brushes.

In Summary,

when thinking about formative program planning and how to apply what you learned in this chapter to your program you may want to ask:

- Is it feasible for me to form a planning and evaluation team?

- If yes – what partners and stakeholders should be invited to join the planning and evaluation team?

- If yes – who should be selected as the team leader?

- Who could I form partnerships with to help with the success of the program and/or the evaluation?

- Who is my target audience?

- What do I need to know about my target audience (attitudes, behaviors, interests etc.)? Can I conduct a needs assessment?

- What behavior theories could be applied to help me understand more about the food safety behaviors of my target audience?

- What are the core activities of my program?

- What are the core messages of my program?

- How will core messages be disseminated (delivery channel/timing/type of materials)?

- How can I ensure that program activities and messages take health literacy and cultural sensitivity into account?

References

- Armitage, C. J., Sheeran, P., Conner, M., & Arden, M. A. (2004). Stages of change or changes of stage? Predicting transitions in transtheoretical model stages in relation to healthy food choice. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(3), 491–499.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

- Bemis, K. M., Marcus, R., & Hadler, J. L. (2014). Socioeconomic status and campylobacteriosis, Connecticut, USA, 1999-2009. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 20(7), 1240-1242.

- Borrusso, P., & Das, S. (2015). An examination of food safety research:

implications for future strategies: preliminary findings. Partnership for Food Safety Education Fight BAC! Forward Webinar. Retrieved from: http://www.fightbac.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Fight-BAC-Forward-Webinar-Slides.pdf - Cates, S., Blitstein, J., Hersey, J., Kosa, K., Flicker, L., Morgan, K., & Bell, L. (2014). Addressing the challenges of conducting effective supplemental nutrition assistance program education (SNAP-Ed) evaluations: a step-by-step guide. Prepared by Altarum Institute and RTI International for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. Retrieved from: http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/SNAPEDWaveII_Guide.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC). (2016). Health literacy: develop materials. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/developmaterials/index.html

- Champion, V.L., & Skinner, C.S. (2009). The health belief model. In: Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K, & Viswanath, K. Health behavior and health education theory, research and practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass,

- Consumer Federation of America (CFA). (2013). Child Poverty, Unintentional Injuries, and Foodborne Illness: Are Low-Income Children at Greater Risk? Retrieved from: http://www.consumerfed.org/pdfs/Child-Poverty-Report.pdf

- Gabor, G., Cates, S., Gleason, S., Long, V., Clarke, G., Blitstein, J., Williams, P., Bell, L., Hersey, J., & Ball, M. (2012). SNAP education and evaluation (wave I): final report. Prepared for U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Research and Analysis. Alexandria, VA. Retrieved from: http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/SNAPEdWaveI.pdf

- Kutner, M., Greenberg, E., Jin, Y., & Paulsen, C. (2006). The health literacy of America’s adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2006-483). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from: https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2006483

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2015). Food Safety: it’s especially important for at-risk groups. Retrieved from: http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodborneIllnessContaminants/PeopleAtRisk/ucm352830.htm

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). White Paper on Consumer Research and Food Safety Education. (DRAFT).

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison—Wesley.

- Fisher, P.A., & Ball, T. J. (2002). The Indian family wellness project: An application of the tribal participatory research model. Prevention Science, 3, 235-240.

- Issel L. (2004). Health Program Planning and Evaluation: A Practical, Systematic Approach for Community Health. London: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

- McDonald, D. A., Kutara, P. B. C., Richmond, L. S., & Betts, S. C. (2004). Culturally respectful evaluation. The Forum for Family and Consumer Issues, 9(3).

- McKenzie J. F, & Smeltzer J. L. (2001) Planning, implementing, and evaluating health promotion programs: a primer, 3rd ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Meysenburg R, Albrecht J., Litchfield, R., & Ritter-Gooder, P. (2013). Food safety knowledge, practices and beliefs of primary food preparers in families with young children. A mixed methods study. Appetite, 73, 121-131.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S National Library of Medicine, MedlinePlus. (2016). How to write easy-to-read health materials. Retrieved from https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/etr.html

- Nielsen-Bohlman, L., Panzer, A. M., & Kindig, D. A. (Eds.). (2004). Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- O’Connor-Fleming, M. L., Parker, E. A., Higgins, H. C., & Gould, T. (2006) A framework for evaluating health promotion programs. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 17(1), 61-66.

- Po, L. G., Bourquin, L. D., Occeña L. G., & Po, E. C. (2011). Food safety education for ethnic audiences. Food Safety Magazine. 17, 26-31.

- Prochaska, J.O. , Redding, C.A., & Evers, K. E. (2008). The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K, Vinswath, K. Health behavior and health education theory, research and practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Rice, R. E., & Atkin, C. K. (2001). Public Communication Campaigns. London: Sage publications.

- Rudd, R. E., Anderson, J. E., Oppenheimer, S., & Nath, C. (2007). Health literacy: An update of public health and medical literature. In J. P. Comings, B. Garner, & C. Smith. (Eds.), Review of adult learning and literacy, 7, 175–204. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Stubben, J.D. (2001). Working with and conducting research among American Indian families. American Behavioral Scientist, 44, 1466-1481.

- S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2010). National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy. Washington, DC. Retrieved from: https://health.gov/communication/initiatives/health-literacy-action-plan.asp

- Whitney, B. M., Mainero, C., Humes, E., Hurd, S., Niccolair, L., & Hadler, J. L., (2015). Socioeconomic status and foodborne pathogens in Connecticut, USA, 2001-2011. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 21(9), 1617-1624.